Assessing the health and sociological impacts of a Basic Income Grant

By Brendan Maughan-Brown

“My government’s commitment to create a people-centred society of liberty binds us to the pursuit of the goals of freedom from want, freedom from hunger, freedom from deprivation, freedom from ignorance, freedom from suppression and freedom from fear. These freedoms are fundamental to the guarantee of human dignity. They will therefore constitute part of the centrepiece of what this government will seek to achieve, the focal point on which our attention will be continuously focused.”

State of the nation address by the President of South Africa, Nelson Mandela

Houses of Parliament, Cape Town, 24 May 1994

As part of SALDRU’s mission to reduce inequalities through policy-relevant research, we have led many studies of the social protection system in South Africa, including various social grants. In the absence of job-security – with approximately 33.5% unemployment (Maluleke 2024) – these grants remain central to achieving the freedoms President Mandela committed the government to achieving in his first State of the Nation Address.

When COVID-19 hit there was a need to react quickly to massive job losses and concurrent increases in poverty rates. SALDRU contributed to discussions that led to the Special COVID-19 Social Relief of Distress (SRD) grant. The SRD was the first social grant in South Africa intended for unemployed individuals who are working-aged and able-bodied. In contrast to other social grants that reached women and children or the elderly, the SRD grant offered support to working-age men who were previously excluded from the social security system.

The initial value of the grant was R350 per month, roughly one quarter to one fifth of the upper bound poverty line, and just 6% of the median monthly wage (Bhorat & Köhler 2024). The SRD grant amount was recently increased to R370. Simulations of the December 2021 receipt of the SRD grant suggested that the programme substantially mitigated pandemic unemployment-induced poverty, with most of its effect occurring at the bottom end of the income distribution (Bassier et al. 2022). While it reduced household hunger, the SRD grant did not provide food security for most households. In addition, contrary to popular belief, the SRD grant did not discourage employment. Researchers showed that receipt of the SRD grant led to short-term gains in employment, but longer-term gains were not evident (Bhorat et al. 2023).

In 2021, the key question arose as to whether the SRD grant should be continued, and, if not, what other options were available for further reducing poverty and inequality. SALDRU was asked to join a National Treasury working group to conduct a modelling analysis of different anti-poverty programs. These included: increasing the value of the Child Support Grant; continuing the SRD grant; introducing a Basic Income Grant (BIG); introducing a household-based Family Poverty Grant; and either introducing a new Public Works Programme or expanding the existing programmes (Goldman et al. 2021). A Basic Income Grant (also called Universal Basic Income) would be an unconditional, monthly cash payment to all South Africans, with the value based approximately on the South African poverty line (±R1500). One key finding from the modelling analysis was that the BIG would have the largest impact on poverty and would be relatively easy to implement through banking systems and other modes of delivery. However, the modelling analyses also found that the BIG is the least efficient and most expensive option for reducing extreme poverty, even though it will have the largest total impact on poverty (Goldman et al. 2021). This conclusion was based on a narrow focus on the economic benefits it would bring. A key conclusion from the working group was that there is an urgent need to consider the full set of benefits and consequences of a BIG, not from just an economic perspective, but also from sociological and health perspectives.

As the debate on a BIG in South Africa continues, it becomes increasingly clear that high-quality evidence on the social and health impacts of a BIG will be essential for making the right decision. Without considering the many potential positive impacts on health and social outcomes, and the associated cost savings to the government (for example, from not needing to treat disease that is prevented), there will remain a blind-spot in our opinions about whether South Africa should introduce a BIG.

In response, SALDRU is partnering with colleagues Harsha Thirumurthy and Aaron Richterman at the University of Pennsylvania to develop a proposal for a large, clustered, randomized control trial of the impact of a cash transfer equivalent to the poverty line (matching proposed amounts for a BIG) on health and social outcomes.

Poverty is widely recognized as an important social determinant of health. Numerous studies have documented an association between poverty and poor health outcomes. The disparities in health outcomes between the rich and poor are substantial: in South Africa, the gap in life-expectancy between the richest 20% and the poorest 20% of individuals in 2014 was nearly 14 years (Bredenkamp et al. 2021). This disparity exists despite substantial scale-up of HIV treatment and other health services. While continued expansion of access to healthcare services is essential for improving health outcomes, there is growing evidence that doing so without addressing poverty will not close the large gaps in health outcomes between the rich and poor.

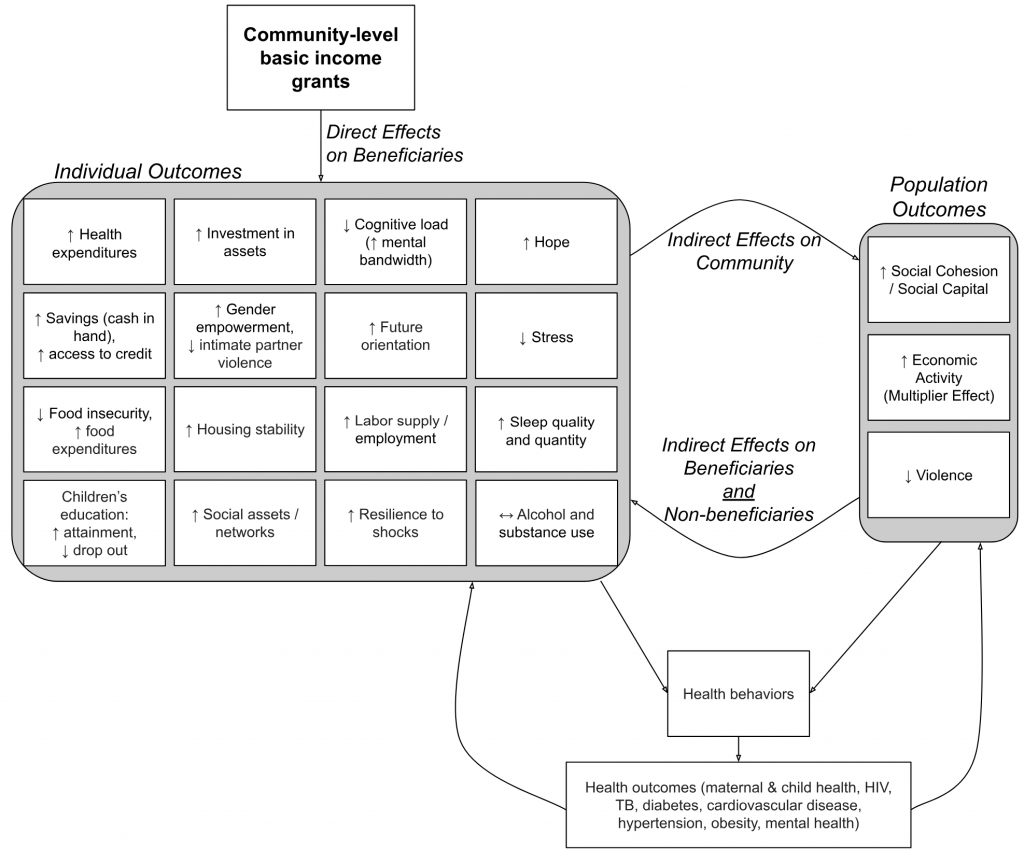

There are numerous pathways through which poverty influences health outcomes. At the individual level, these include economic pathways (for example, poverty affects food security and healthcare access) and psychological pathways (e.g., financial stress affects one’s ability to prioritize health-promoting behaviours). At the community or population level, higher poverty levels can also lead to increased transmission of infectious diseases. There are therefore numerous pathways through which a BIG could improve multiple outcomes. Figure 1 provides a rough draft of some potential high-level pathways. An example of one of the more detailed pathways illustrates the potential impact of a BIG on multiple outcomes. One reason for dropping off medication, or sub-optimal adherence to medication, such as HIV treatment, is not being able to take treatment with an empty stomach. Increasing food security could therefore decrease morbidity and mortality from AIDS-related illnesses and decrease new HIV infections (as HIV transmission is nearly eliminated through good treatment-adherence). At the same time, increased food expenditure may result in more nutritious food being consumed and decrease the risk of diabetes in the population. Far-reaching societal changes, including increased social cohesion, may occur through reductions in crime and violence.

We are at the early stages of developing the research proposal. Key study objectives include: determining the impact of basic income grants on health behaviours and health outcomes; assessing psychological and economic factors that mediate the effect (or lack of effect) of basic income grants on health outcomes; and conducting a cost-benefit analysis of this poverty-alleviation approach. Initial discussions with research funding agencies indicate a strong potential for funding to support the evaluation component of the project. We are also exploring several partnerships for funding for the cash transfer component of the intervention.

We are hopeful that our research will not only provide evidence on a strategy that supports the goals expressed in President Mandela’s State of the Nation Address of freedom from want, hunger, and deprivation, but also that it will support the goal of freedom from poor mental and physical health.

For more information, or to discuss further, please contact Dr Brendan Maughan-Brown: Brendan.maughan-brown@uct.ac.za

References

Bassier, I., Budlender, J. & Goldman, M., 2022. Social distress (some) relief: Estimating impact pandemic job loss poverty South Africa. SA-TIED Working Paper #210. Available at: https://sa-tied.wider.unu.edu/sites/default/files/SA-TIED-WP210.pdf.

Bhorat, H. & Köhler, T., 2024. The Labour Market Effects of Cash Transfers to the Unemployed: Evidence from South Africa. Development Policy Research Unit Working Paper 202405. DPRU. University of Cape Town. Available at: https://commerce.uct.ac.za/sites/default/files/media/documents/commerce_uct_ac_za/1093/dpru-wp202405.pdf.

Bhorat, H., Köhler, T. & de Villiers, D., 2023. Can Cash Transfers to the Unemployed Support Economic Activity? Evidence from South Africa. Development Policy Research Unit Working Paper 202301. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/dpruwp202301.

Bredenkamp, C. et al., 2021. Changing inequalities in health-adjusted life expectancy by income and race in South Africa. Health systems and reform, 7(2), p.e1909303.

Goldman, M. et al., 2021. Simulation of options to replace the special COVID-19 Social Relief of Distress grant and close the poverty gap at the food poverty line. WIDER Working Paper 2021/165.

Maluleke, R., 2024. Quarterly Labour Force Survey (QLFS) Q2:2024, Statistics South Africa. https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0211/Presentation%20QLFS%20Q2%202024.pdf